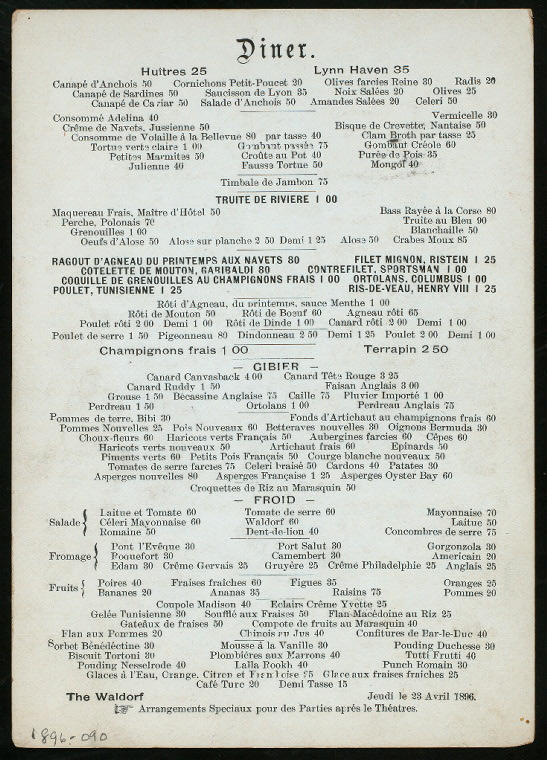

From vehemently rejecting the French word “menu” to using the very same word matter-of-factly in the title of one’s book—much can change in a few years. In The Culinary Handbook: The Most Complete and Serviceable Reference Book to Things Culinary Ever Published (1904) by Charles Fellows, the entry for “menu” protests the usage of this and other French culinary terms in American restaurants. The author favors “bill of fare” instead. Yet the next book by Charles Fellows would have as its title The Menu Maker: Suggestions for Selecting and Arranging Menus for Hotels and Restaurants, with Object of Changing from Day to Day to Give Continuous Variety of Foods in Season; A Reminder for the Breakfast, Luncheon, Dinner, and Supper Cards, Together with Brief Notations of Interest to the Proprietor, Steward, Headwaiter and Chef (1910). This about-face by Charles Fellows regarding one word does not exactly reflect how using French culinary terms was still debated at the turn of the twentieth century. In nineteenth-century America, restaurants were at first typically establishments for the upper-class. A menu written in French was not difficult for them to decipher, but as the purchasing power of the middle-class grew during the latter part of the century, frustration with ordering in French at restaurants became an issue that eventually resulted in bilingual menus and then even menus entirely in English. In New York City, for example, the Waldorf Hotel’s dinner menu was a bilingual one in 1896, and the St. Regis Hotel’s menu was translated into English by 1905. The 1838 Carte du restaurant français des frères Delmonico in both English and French was a much earlier pioneer.

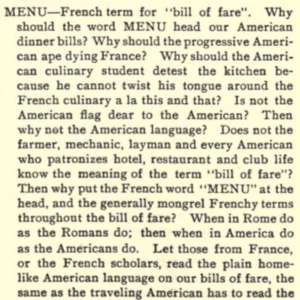

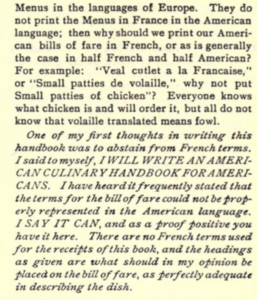

“MENU.” Entry from page 107 of The Culinary Handbook: The Most Complete and Serviceable Reference Book to Things Culinary Ever Published (1904) by Charles Fellows. https://archive.org/details/culinaryhandbook00felliala/page/106/mode/2up

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “DINNER [held by] THE WALDORF [at] “[NEW YORK, NY]” (HOTEL;)” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47db-2ac0-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

▀▄▀▄▀▄

References & Suggested Reading

Fellows, Charles. The Chef’s Reminder. A Culinary Book for the Vest Pocket. Chicago, n.p., 1895.

– – – . The Culinary Handbook: The Most Complete and Serviceable Reference Book to Things Culinary Ever Published. Chicago, Hotel Monthly, 1900.

– – – . The Menu Maker. Appendix … Menus and Bills of Fare. Chicago, Hotel Monthly, 1924.

– – – . The Menu Maker: Suggestions for Selecting and Arranging Menus for Hotels and Restaurants, with Object of Changing from Day to Day to Give Continuous Variety of Foods in Season; A Reminder for the Breakfast, Luncheon, Dinner, and Supper Cards, Together with Brief Notations of Interest to the Proprietor, Steward, Headwaiter and Chef. Chicago, Hotel Monthly Press, 1910.

– – – . A Selection of Dishes and the Chef’s Reminder. Chicago, Hotel Monthly Press, 1909.

Haley, Andrew. “ ‘I Want to Eat in English’: The Middle Class, Restaurant Culture, and the Language of Menus, 1880–1930.” Midwestern Folklore 29, 2003, pp.25–39.

– – – . Turning the Tables: Restaurants and the Rise of the American Middle Class, 1880-1920. United States, University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

“Obituary: The Passing of Charles Fellows.” Hotel Monthly, October 1921, vol. 29, no. 343, p.66.

Portes, Jacques. “Huîtres, frites, ice-cream et eau glacée (les Français et la cuisine américaine, 1870-1914).” Revue Française d’Etudes Américaines, N°27-28, février 1986, pp. 15-36. Persée, https://doi.org/10.3406/rfea.1986.1218

Teller, Joan W. “The Treatment of Foreign Terms in Chicago Restaurant Menus.” American Speech, vol. 44, no. 2, 1969, pp. 91–105. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/455099.