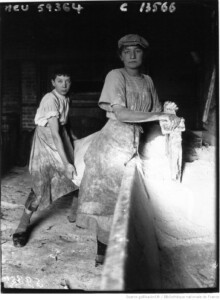

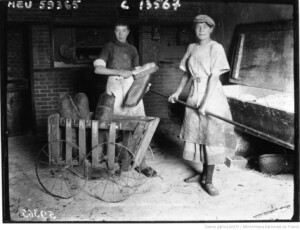

Mobilization in France during World War I meant that villages could suddenly lose their only bread baker, among other essential workers. As it was not customary for anyone to make their own bread at home, losing the source of this daily staple food caused great concern. In certain cases, the baker’s young children decided to continue their father’s work, because they knew how much the village depended on them for sustenance. In the village of Exoudun, Madeleine Daniau was fifteen years old when her father went off to war in 1915, and so she started waking up at four o’clock in the morning to bake four hundred kilos (the equivalent of almost eight hundred eighty-two pounds) of bread that the village needed. She had a younger brother who worked alongside her; their mother was already deceased by then. Word of Madeleine’s efforts even reached Paris, where newspapers regarded her work as heroism. The president of France sent her a letter of congratulations after the prefect of Deux-Sèvres had spoken to him about her. A less well-known case is that of Louis Raimbault from the village of Villecerf. In 1914, at the age of thirteen, he began trying his hand at baking bread, despite his mother’s protestations that he was not strong enough to do everything that his baker father did. The father had to report to his regiment on one day’s notice. After a few burnt loaves and instances of not using enough salt, the young son eventually produced enough successful loaves to supply the village on a regular basis. Later on, with an assistant, he was able to bake bread on a larger scale to feed refugees who came to his village during the Battle of the Marne. He also supplied bread to the nearby village of Bormelles when it became in need of this staple food during the war.

Madeleine Danniau, boulangère à Exoudun, remplaçant son père mobilisé : [photographie de presse] / Agence Meurisse. 1916. Bibliothèque nationale de France → https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b90444053

Madeleine Danniau, boulangère à Exoudun, fabriquant du pain : [photographie de presse] / Agence Meurisse. 1916. Bibliothèque nationale de France → https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41573120j

▀▄▀▄▀▄

References & Suggested Reading

Barrès, Maurice. L’ âme française et la guerre. Paris: Émile-Paul frères, 1918.

Collins, Ross F. “Justifying War: American children’s publications and the First World War.” North Dakota State University, Fargo, USA. https://www.ndsu.edu/pubweb/~rcollins//491americanpower/childrenspubsinwwI.pdf

Deschamps, E. “Notre pain.” Le Protestant béarnais, no. 11, 4 novembre 1916, p. 77.

Donnay, Maurice. Premières impressions ; Après. Paris & Zürich: Crès, 1917.

Du Genestoux, Magdeleine. La France en guerre: a French reader for elementary classes. Boston & New York: Allyn and Bacon, 1922.

Guyon, Charles. Les Petits héros de France. Paris: Larousse, 1916.

“La petite boulangère d’Exoudun.” Le Petit journal (Paris), 30 août 1915, p. 1.

“La petite boulangère d’Exoudun.” Le Radical (Paris), 21 septembre 1915, p. 2.

“Les obsèques de la petite boulangère.” Le Rappel (directeur gérant : Albert Barbieux), 13 avril 1920, p. 4.

Mountsier, Robert DeMain, and Mabel Louise Mountsier. “Three Loyal Children of France.” St. Nicholas, vol. XLIV, no.9, July 1917, pp. 780-2.

Perreux, Gabriel. La Vie quotidienne des civils en France pendant la grande guerre. Paris: Hachette, 1966.

Société d’études folkloriques du Centre-Ouest. Aguiaine (Revue de recherches ethnographiques), Vol. 13, mars-avril 1979. France, La Société, 1979.

Société historique et scientifique (Deux-Sèvres). Bulletin de la Société historique et scientifique des Deux-Sèvres. 1 janvier 1919.

Texier, André. Essai d’histoire municipale de Niort : De 1914 à 1924. France, Editions du Terroir, 1982.

“Un bel exemple de dévouement.” La Dépêche algérienne : journal politique quotidien, 21 septembre 1915, p. 1.