The pear motif in caricatures of King Louis-Philippe I (1773-1850) that were drawn by Charles Philipon (1800-1862) and his fellow caricaturists has been analyzed by critics from many angles, but an approach that seems not to have been taken up much at all is one focusing on a number of those cartoons that play with notions of eating, not eating, preparing, and cooking pears. When satirically blending what needs to be rejected (a repressive monarchy) with what is usually related to nourishment (pears, eating, cooking, a dining table, a kitchen, a garden), such a cartoon can unsettle readers enough to make them see that political change needs to be made. Moreover, the suggested violence in these cartoons emerges in startling yet “familiar” ways.

▀▄▀▄▀▄

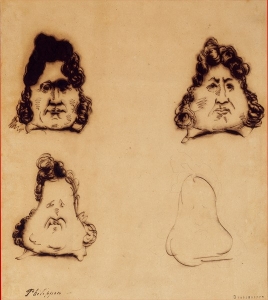

Before taking a look at a number of the cartoons, a quick summary of how the pear became embroiled in the politics of nineteenth-century France is in order. Charles Philipon was a lithographer, caricaturist, journalist, and editor of two journals that were quite satirical: the weekly La Caricature (1830-1835) and the daily Le Charivari (1832-1937). Censorship laws during Louis-Philippe’s reign (1830-1848) grew increasingly oppressive for political caricaturists, as many were arrested, put on trial, fined, and jailed. While in court on November 14, 1831 Philipon argued that cartoons published in La Caricature should not be interpreted as harmful to the king because any object can be drawn to resemble the king’s face or anything else for that matter. Philipon chose to prove his point by sketching a pear.

Charles Philipon. La Métamorphose du roi Louis-Philippe en poire. Paris: 1831. Bibliothèque nationale de France → https://expositions.bnf.fr/daumier/grand/017_2.htm

Less than two weeks after the trial he published in La Caricature the pear-king comparison that he had used in court, and he was subsequently arrested, ordered to pay fines, and sentenced for six months. Following this initial sentence Philipon was quickly jailed again for seven more months, one of his new offenses being the publication of his cartoon “Projet d’un monument expia-poire” (La Caricature, 7 June 1832) which shows a pear monument in the Place de la Révolution (Paris) where Louis XVI had been guillotined in 1793. The monarchy viewed this cartoon as a great threat and slyly made Philipon serve part of his second sentence in Dr. Pinel’s Maison de santé (France’s early attempt at creating a mental hospital), the message to the country being that only someone with a mental disorder would draw cartoons to ridicule the king. Philipon’s fellow caricaturist Honoré Daumier (1808-1879), whose biting work appeared in La Caricature as early as 1830, had also made great use of the unflattering pear motif, though his arrest in 1832 was for having drawn the cartoon “Gargantua” (1831) which depicts a corrupt Louis-Philippe I. Like Philipon, Daumier had to spend part of his sentence in a mental hospital. Nonetheless, the pear motif would soon be used throughout France as a taunting symbol of resistance, from being drawn on walls in Paris’ Latin Quarter and on prison walls to appearing in Stendhal’s novel Lucien Leuwen (1894) when certain inhabitants of Nancy decide to humiliate a general that they dislike by showing him pears.

▀▄▀▄▀▄

An early cartoon that made cutting a pear seem dangerous was drawn by Charles-Joseph Traviès (1804-1859) and published in La Caricature in April 1832, less than two years after Louis-Philippe had become king. In this cartoon Monsieur Mahieux (a jester of a character used by artists to avoid censorship) is about to slice a pear’s “neck,” suggesting that Louis-Philippe I should be killed for breaking his promise to heed the Charter of 1830, a document that had been created to limit the powers of the king. The ordinariness of the setting (a dining table, a bottle of wine, a chair, etc) brings the reader closer to Monsieur Mahieux’s stance. This depiction of a one-on-one encounter with the king suggests that the ordinary citizen has that much more power to act. Regicide was not unthinkable in 1832, given that La Terreur (The Reign of Terror) was still rather fresh in people’s memories. During the French Revolution (1789-1799) there was a period in which tens of thousands of people who had opposed the revolution were executed from September 1793 to July 1794 —La Terreur. Louis-Philippe’s father was one of the many aristocrats who had been guillotined.

Charles-Joseph Traviès. “Ah ! scélérate de poire pourquoi n’es-tu pas une vérité !” ou M. Mahieux poiricide : il s’apprête à couper la poire qui n’a pas tenu ses promesses. Paris: n.p., 1832. Bibliothèque nationale de France → https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41518590s

▀▄▀▄▀▄

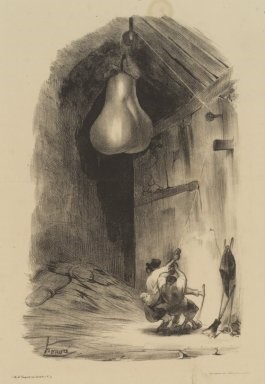

Three months after Traviès’ cartoon appeared, one by Honoré Daumier in La Caricature would depict a small group of ordinary citizens using all of their might to hoist (hang) an enormous pear rather than eat it. This cartoon was interpreted by the monarchy as yet another hint at regicide. Interestingly, it was only in the late nineteenth century that the pear became more affordable (and thereby less of a luxury fruit). “Des hommes du peuple”— ordinary citizens— in 1832 France would most likely have loved to eat pears. Something must have been grossly wrong with this particular “pear” that people would reject “eating” it.

Honoré Daumier. “Heave-ho!…Heave-ho! Heave-ho!… (Ah! His!… Ah ! His ! Ah ! His !…),” alternative title “Une énorme poire pendue par des hommes du peuple.” July 19, 1832. Brooklyn Museum, New York. → https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/49238

▀▄▀▄▀▄

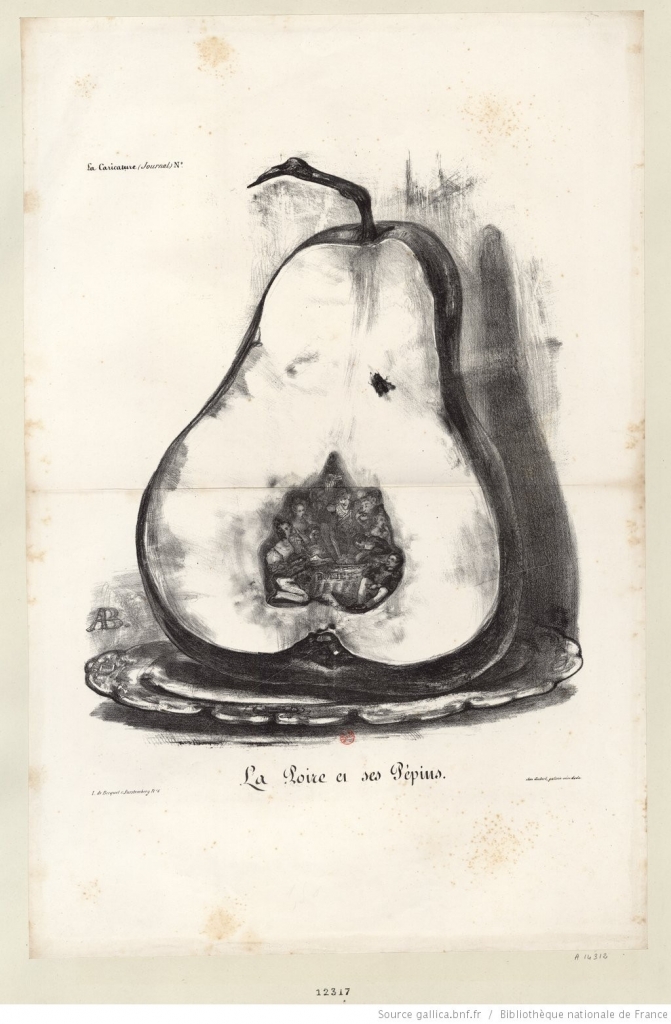

Who were the ones who had the opportunity to feast during the reign of Louis-Philippe I? A July 1833 cartoon by Auguste Bouquet (1810-1846) in La Caricature has the answer: princes, the queen, and princesses are depicted as gorging on the country’s budget. Ordinarily seeds are a source of potential fruitfulness, but the “bad seeds” exposed in this cartoon are an expression of current harm that will lead to the country’s ruin.

Auguste Bouquet. La Poire et ses Pépins. Paris: Chez Aubert, Galerie Véro-Dodat, 1833. Bibliothèque nationale de France → https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41518581t

▀▄▀▄▀▄

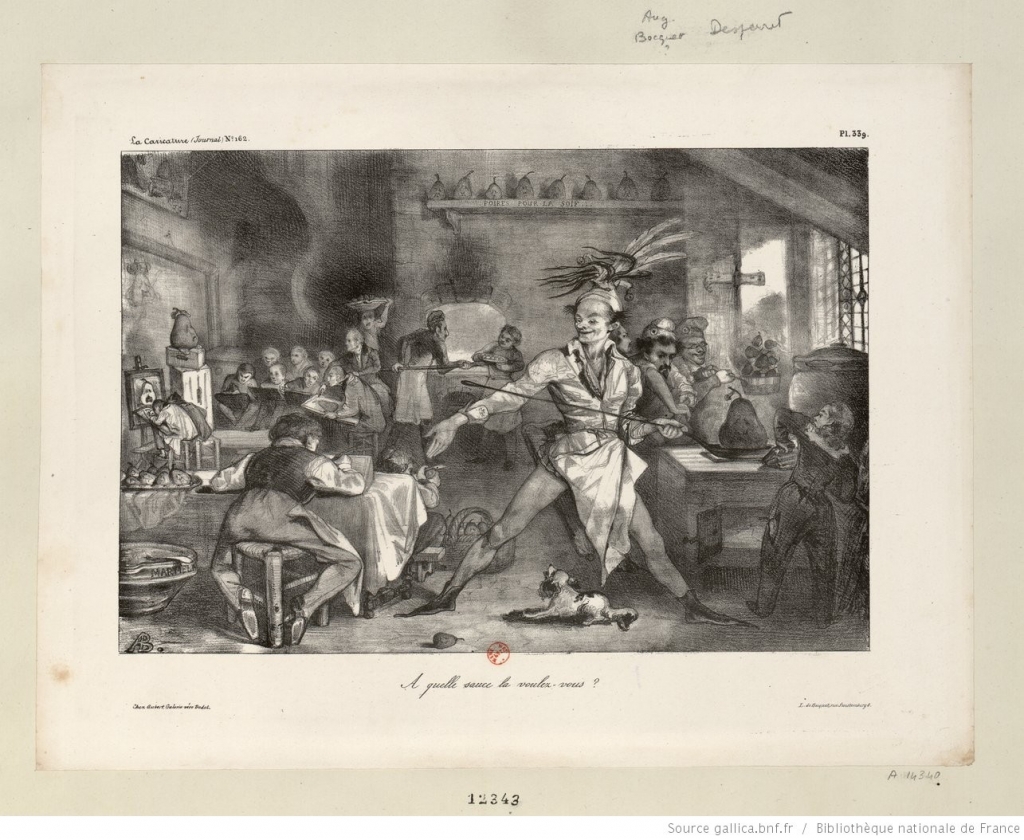

In a December 1833 cartoon Auguste Bouquet depicts a kitchen where his co-workers at La Caricature (Grandville, Forest, Traviès, Daumier, Benjamin, l’enfant Jean-Paul, Desperret, Philipon, among others) draw, color, shade pears as well as knead, wash, and cut up several more. Philipon as chef asks his fellow artists what type of sauce they would like to use for a pear that is about to be cooked, whether fried, stewed, poached, or baked. The pear by itself, like Louis-Philippe I, is unpalatable in this menacing yet playful cartoon. Here artists are no longer as powerless against the king as they would usually be.

Auguste Bouquet. “A quelle sauce la voulez-vous ?” demanda “le grand cuisinier en chef Philipon”, dans la cuisine de la “Caricature”, au moment de la préparation, friture et cuisson de la poire. Paris: Chez Aubert, Galerie Véro-Dodat, 1833. Bibliothèque nationale de France → https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41518607p

▀▄▀▄▀▄

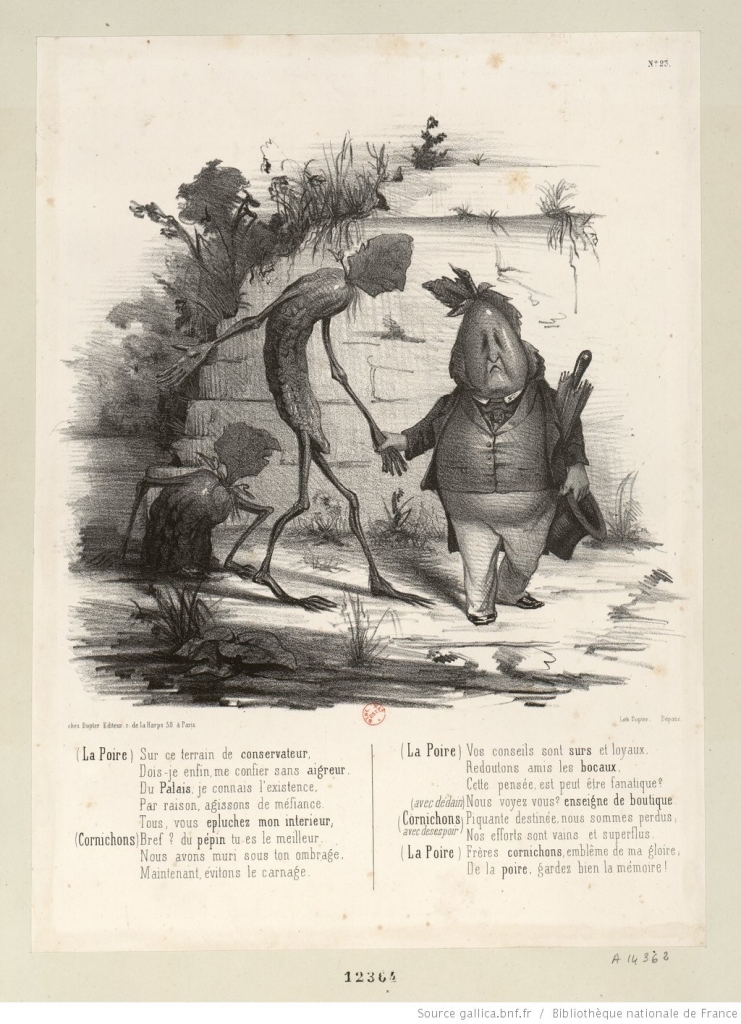

Pickled! During the February 1848 Revolution Louis-Philippe I abdicated and fled France. A cartoon from that very year shows him having a disillusioned conversation with two of his cabinet members: François Guizot (1787-1874), Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Tanneguy Duchâtel (1803-1867), Minister of the Interior. All three express their fear of becoming packed into a jar and pickled, with Louis-Philippe the Pear anguished at the thought of being cored as well. Recipes for making poires au vinaigre and poires confites au vinaigre can call for the pears to be peeled as well. Vinegar splashing on a small wound would create enough of a stinging sensation, to say nothing of how it may feel to be flayed and then soaked in a vinegary liquid. Flaying was actually still used as a form of punishment in France as recently as the eighteenth century, as Michel Foucault notes in Surveiller et punir : Naissance de la prison (1975). If this cartoon is not really advocating such violence, it at least expresses the intense punishment that the citizens felt that Louis-Philippe I deserved for the ways in which he had badly ruled the country. The expression “tourner au vinaigre” would also apply here in that Louis-Philippe I is now in a predicament that has taken a turn for the worse.

Jean Vincent Marie Dopter. (La Poire) Sur ce terrain de conservateur / Dois-je enfin, me confier sans aigreur. Paris: Chez Dopter, 1848. Bibliothèque nationale de France → https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41518628n

▀▄▀▄▀▄

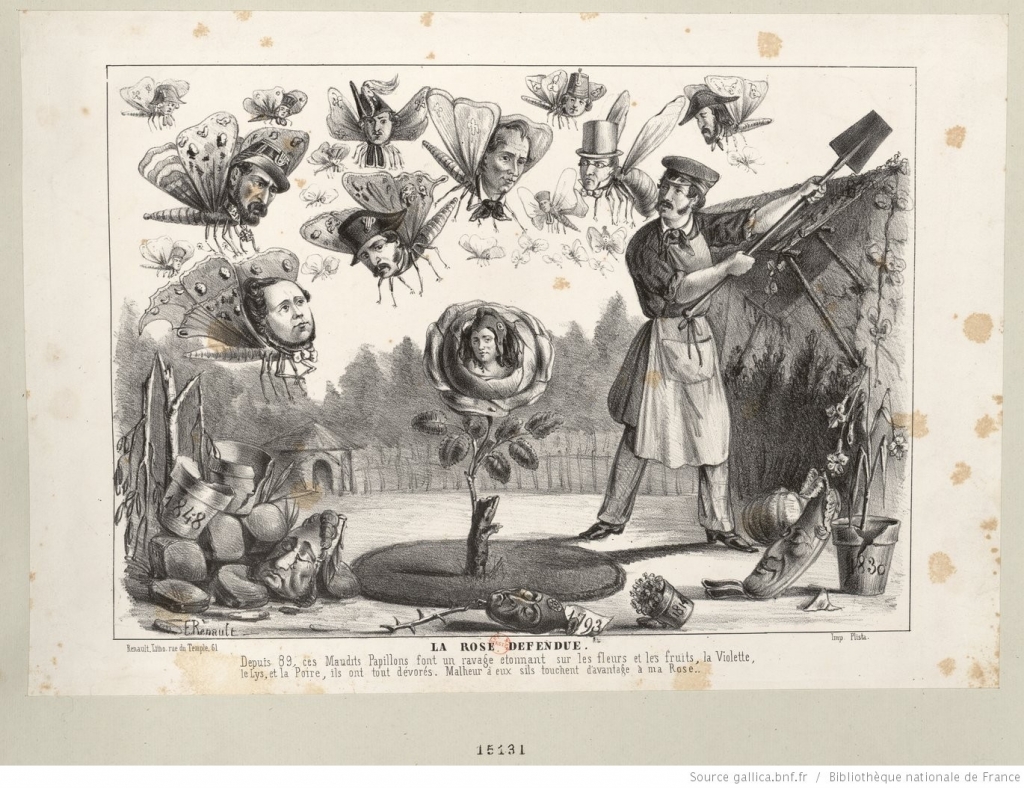

Last but not least, a rotting pear of a Louis-Philippe I can still be considered food…for certain butterflies, that is. In an 1848 cartoon E. Renault depicts a gardener ready to protect the French Republic (in the center of the rose) from men who are hungry to establish powerful positions for themselves after the fall of Louis-Philippe’s reign. The butterflies are identified as Ledru-Rollin, Cavaignac, Louis-Napoléon, le comte de Chambord, Lamartine, le prince de Joinville, le comte de Paris, Thiers, and Dupin. Though butterflies generally feed on nectar plants, they can also feed on overripe or rotting fruit. Yet the butterflies in Renault’s cartoon are not eating the rotting pear that has fallen onto the ground. Butterfly larvae feeding on a rose bush can easily damage it, but how would adult male butterflies (which do not lay eggs) be dangerous to a rose bush? One can argue that these men will exhibit parasitic behavior once they succeed in gaining government positions again.

E. Renault. La rose défendue, Depuis 89, ces Maudits Papillons font un ravage étonnant sur les fleurs et les fruits, la Violette, le Lys, et la Poire, ils ont tout dévorés [sic]. Paris: Renault, 1848. Bibliothèque nationale de France → https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41521276x

▀▄▀▄▀▄

Interestingly, in the early part of the twentieth century the word “poire” itself acquired new meanings that bring to mind Philipon’s pear. The dictionary Le Trésor de la langue française notes that the word “poire” can mean a person who is easily duped, whose intellect needs to be much improved, as the word is used in Jules Renard’s novel L’Œil clair (1910) when an “imbécile” is a “poire.” Le Trésor de la langue française also acknowledges that “poire” can mean a person’s face, an early example given being Céline’s usage in his novel Voyage au bout de la nuit (1932). Even a verb was created: “poirer” (1916) as noted in Gaston Esnault’s dictionary of slang Le poilu tel qu’il se parle (1919), meaning to catch someone by surprise. One need only imagine how Louis-Philippe I reacted when he turned the page to discover that there was yet another pear-shaped caricature of him.

▀▄▀▄▀▄

References & Suggested Reading

Champfleury. Histoire de la caricature moderne, 3ème édition. Paris: E. Dentu, 1885.

Kenney, Elise K., and John M. Merriman. The Pear: French Graphic Arts in the Golden Age of Caricature. South Hadley, Mass.: Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, 1991.

Kerr, David. Caricature and French Political Culture 1830-1848: Charles Philipon and the Illustrated Press. Oxford / New York: Oxford UP, 2000.

Knapp, Vincent J. “Major Dietary Changes in Nineteenth-Century Europe.” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 31.2 (1988): 188-193.

Margadant, Jo Burr. “Gender, Vice, and the Political Imaginary in Post-Revolutionary France: Reinterpreting the Failure of the July Monarchy, 1830-1848.” The American Historical Review 104.5 (1999): 1461-496.

Menon, Elizabeth K. The Complete Mayeux: Use and Abuse of a French Icon. New York: Peter Lang, 1998.

Petrey, Sandy. In the Court of the Pear King: French Culture and the Rise of Realism. Ithaca and London: Cornell UP, 2005.

Stendhal. Lucien Leuwen, édition établie at annotée par Anne-Marie Meininger. Paris: Gallimard, 2011.

Terdiman, Richard. Discourse/Counter-Discourse: The Theory and Practice of Symbolic Resistance in Nineteenth-Century France. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1985.