In 1814 General Andrew Jackson urgently needed more soldiers in order to be able to fight off the British who were trying to take New Orleans. On September 21st he appealed to the freemen of color in Louisiana to enlist. He promised them that their valor would be made known throughout the country and that they would receive the same payment as would white soldiers. Of the hundreds who enlisted, many were French-speaking Creoles originally from Martinique and Haiti. Jackson also traveled to plantations with the goal of enlisting five hundred enslaved men: he promised them their freedom if they would aid in preventing the British from taking New Orleans. After the British were defeated, Jackson reneged on his promises. Moreover, those freemen whose homes were in New Orleans were forced to leave the city after the war, to suit the preference of influential racists there. It was thirty-six years after the battle at Chalmette was won that ninety freemen of color veterans were invited to the annual January 8th parade. What can one do when dealt with such a hand? Put pen to paper: try to express that horrible yet freeing moment of realization that one has been deceived, betrayed. Make the lines speak such truth that the poem is spread by word of mouth as well as put into family copybooks, even if more than seventy years will pass before it enters print publication:

Après avoir remporté la victoire,

Dans ce terrible et glorieux combat,

Vous m’avez tous, dans vos coups, fait boire,

En m’appelant un valeureux soldat.

Moi, sans regret, avec un cœur sincère,

Hélas ! j’ai bu, vous croyant mes amis ;

Ne pensant pas, dans ma joie éphémère,

Que je n’étais qu’un objet de mépris.

(Click here for an English translation and to read the rest of the poem “La Campagne de 1814-15”)

Was Hippolyte Castra the pseudonym or the actual name of the person who wrote the poem “La Campagne de 1814-15”? Written before 1840, why did the poem not see print until 1911 in Nos hommes et notre histoire : notices biographiques accompagnées de reflexions et de souvenirs personnels, hommage à la population créole, en souvenir des grands hommes qu’elle a produits et des bonnes choses qu’elle a accomplies by Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes (1849-1928)? Finding answers to these questions and others is important, but the stanza above brings the reader ever closer to what so many men must have felt.

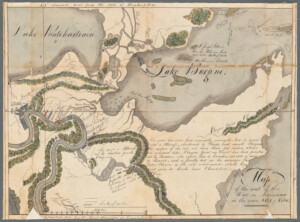

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Map of the seat of the War in Louisiana in the years 1814 + 1815.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1815-1820. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/f6bf2a80-22d4-0135-1cbd-069c1eb17ff4

▀▄▀▄▀▄

References & Suggested Reading

Bell, Caryn Cossé. Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition in Louisiana, 1718-1868. United States, LSU Press, 1997.

Desdunes, Rodolphe Lucien. Nos hommes et notre histoire : notices biographiques accompagnées de réflexions et de souvenirs personnels, hommage à la population créole, en souvenir des grands hommes qu’elle a produits et des bonnes choses qu’elle a accomplies. Montréal: Arbour & Dupont, 1911.

– – – . Our People and Our History: Fifty Creole Portraits. United Kingdom, LSU Press, 2001.

Johnson, Sara Elizabeth. The Fear of French Negroes: Transcolonial Collaboration in the Revolutionary Americas. University of California Press, 2012.

La marseillaise noire et autres poèmes français des Créoles de couleur de la Nouvelle-Orléans (1862-1869). France, Editions du cosmogone, 2001.

Pratt, Lloyd. The Strangers Book: The Human of African American Literature. United States, University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated, 2016.

Remini, Robert Vincent. Andrew Jackson. United Kingdom, Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Smith, Gene Allen. “Objects of Scorn: Remembering African Americans and the War of 1812.” The Battle of New Orleans in History and Memory, edited by Laura Lyons McLemore. LSU Press, 2016, pp.79-99.

– – – . The Slaves’ Gamble: Choosing Sides in the War of 1812. United States, St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2013.

Thompson, Shirley Elizabeth. Exiles at Home: The Struggle to Become American in Creole New Orleans. United Kingdom, Harvard UP, 2009.