“Dr. Knowles, a physician of worthy character in London, had occasion to recommend a diet to a patient, of which sugar composed a material part. His patient refused to submit to his prescription, and gave as a reason for it, that he had witnessed so much of the oppression and cruelty which were exercised upon the slaves, who made the sugar, that he had made a vow never to taste the product of their misery as long as he lived”—this footnote on page 502 of the 1795 book An Historical, Geographical, Commercial and Philosophical View of the American United States, and of the European Settlements in America and the West-Indies (Vol. 3) by William Winterbotham (1763-1829) communicates the general mentality of Englanders who boycotted sugar grown by enslaved people during the late 1700s and early 1800s. At one point, around thirty thousand housewives were refusing on moral grounds to use such sugar for tea (Everett 144). By 1792, at least three hundred thousand people in England had refused to eat this type of sugar for the same reason (Martone 5).

In America, many Quaker men and women boycotted sugar that had been produced by enslaved people. The Quaker abolitionist John Woolman (1720-1772) made it a point not to eat this type of sugar (Levy 261). Sarah Harrison (1736-1812) and Patience Brayton (1733-1794), both Quaker ministers, rejected using products made by enslaved people and would travel to the South to try to convince slave owners to stop being slave owners. Non-Quakers such as the Boston patrician abolitionist Wendell Phillips (1811-1884) also refused to eat such sugar (Briley 4). Quakers and non-Quakers who sought to end slavery turned to the manufacture and use of maple sugar instead. Free Produce stores selling sugar not made by slave labor and other such produce were opened in Philadelphia, Boston, Wilmington, and New York City, among other cities (Nuremberger 119).

Et en France ? If there was nothing quite like the Anti-Saccarite movement in England or the Free Produce movement in America, if there is a dearth of documentation about French men and women who might have boycotted sugar produced by enslaved people in Saint-Domingue (Haiti), Martinique, Guadeloupe, Guiana, and Île Bourbon (Île de la Réunion), then there were at least two French persons who must have declined to consume this type of sugar: Claude Adrien Helvétius (1715-1771) and Nicolas de Condorcet (1743-1794). In his 1758 book De l’esprit, Claude Adrien Helvétius writes: “On conviendra qu’il n’arrive point de barrique de sucre en Europe qui ne soit teinte de sang humain. Or quel homme à la vue des malheurs qu’occasionnent la culture et l’exportation de cette denrée refuserait de s’en priver, et ne renoncerait pas à un plaisir acheté par les larmes et la mort de tant de malheureux ?” (25) — click here for an English translation. Nicolas de Condorcet’s view of sugar produced in France’s colonies is expressed in his commentary on the following pensée (#169) by Blaise Pascal (1623-1662): “Jamais on ne fait le mal si pleinement et si gaîment que quand on le fait par un faux principe de conscience.” Condorcet writes in 1774/1776: “Arracher des hommes de leur pays par la trahison et par la violence […]. Voilà comme nous traitons d’autres hommes : ce serait une horrible barbarie si ces hommes étaient blancs ; mais ils sont noirs, et cela change toutes nos idées. Le trafiquant en Amérique oublie que les nègres sont des hommes ; […] il viole les droits de la nature […]. Ces crimes sont publics, la loi les tolère, l’opinion ne les flétrit pas. On ose même en faire l’apologie ; sans cela, dit-on, nous ne pourrions avoir du sucre. Eh bien ! Si on ne peut pas en avoir qu’à force de crimes, il faut savoir se passer de sucre, il faut renoncer à une denrée souillée du sang de nos frères.” Interestingly, France did see a homegrown movement against sugar later on in the nineteenth century: the working class was antagonistic towards eating sugar, because sugar was viewed as being too bourgeois.

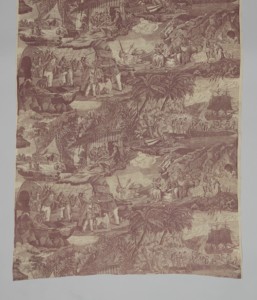

Traite des Nègres (The Slave Trade), early 19th century. Textile designed by Frédéric Etienne Joseph Feldtrappe (1786–1849). After a painting by George Morland (1763–1804). After an engraving by John Raphael Smith (1751–1812) after G. Morland, published in London in 1791. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. → https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/221809

▀▄▀▄▀▄

References & Suggested Reading

Adkins, Gregory Matthew. “Condorcet, Marquis de, (1743-1794).” Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World, edited by Junius P. Rodriguez, Routledge, 2015, pp.139-140.

Bacon, Margaret Hope. “By Moral Force Alone: The Antislavery Women and Nonresistance.” The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s Political Culture in Antebellum America, edited by Jean Fagan Yellin and John C. Van Horne. Cornell UP, 1994, pp.275-297.

Briley, Ron. “Abolitionism and the Civil War.” American Civil War: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection [6 volumes], edited by Spencer C. Tucker. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO, 2013, pp.3-5.

Bruegel, Martin. “A Bourgeois Good? Sugar, Norms of Consumption and the Laboring Classes in Nineteenth-Century France.” Food and Identity: Cooking, Eating and Drinking in Europe Since the Middle Ages, edited by Peter Scholliers, Berg, 2001, pp. 99-118.

Crabtree, Sarah. “In the Light and on the Road: Patience Brayton and the Quaker Itinerant Ministry.” New Critical Studies on Early Quaker Women, 1650-1800, edited by Michele Lise Tarter and Catie Gill, Oxford UP, pp.128-145.

Everett, Susanne. History of Slavery: An Illustrated History of the Monstrous Evil. Chartwell Books, 2014.

Grigsby, Darcy Grimaldo. “Food Chains: French Abolitionism and Human Consumption (1787-1819).” An Economy of Colour: Visual Culture and the North Atlantic World, 1660-1830, edited by Geoff Quilley and Kay Dian Kriz. Manchester UP, 2003, pp.153-175.

Hatcher, Paul E., and Nick Battey. Biological Diversity: Exploiters and Exploited. John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

Helvétius, Claude Adrien. De l’esprit. Paris: Durand, 1758. https://archive.org/details/delesprit03helvgoog/page/n55

– – – . De l’esprit; or, Essays on the mind. Translated from the French. To which are now prefixed, a life of the author and prefatory strictures upon the work, by William Mudford. London: M. Jones, 1807.

Holcomb, Julie L. Moral Commerce: Quakers and the Transatlantic Boycott of the Slave Labor Economy. Cornell UP, 2016.

– – – . “Rejecting the Gain of Oppression: Quaker Abstention and the Abolitionist Cause.” Quakers and Their Allies in the Abolitionist Cause, 1754-1808, edited by Maurice Jackson and Susan Kozel, Routledge, 2016, pp.111-122.

Levy, Barry. Quakers and the American Family: British Settlement in the Delaware Valley. Oxford UP on Demand, 1992.

Lichtenberg, Judith. “Famine, Affluence and Psychology.” Peter Singer Under Fire: The Moral Iconoclast Faces His Critics, edited by Jeffrey A. Schaler, Carus Publishing Company, 2009, pp. 229-266.

Lloyd, Catherine. “Antiracist and Civil Rights Movements.” Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women: Global Women’s Issues and Knowledge, edited by Cheris Kramarae and Dale Spender, Routledge, 2000, pp.72-76.

Martone, Eric. Encyclopedia of Blacks in European History and Culture [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO, 2008.

McDonald, Jack. “Anglicanisme et abolition de l’esclavage dans l’Empire britannique.” Revue d’histoire et de philosophie religieuses, 94e année n°2, avril-juin 2014, pp. 163-176. https://doi.org/10.3406/rhpr.2014.1822

Nuremberger, Ruth Ketring. The Free Produce Movement: A Quaker Protest Against Slavery. New York: AMS Press, 1970.

Pascal, Blaise. Pensées de Blaise Pascal, avec les remarques de Voltaire et de Condorcet, et précédées d’une notice biographique, par P.R. Augus. Tome second. Paris: Froment, 1823.

Pilcher, Jeffrey M., ed. The Oxford Handbook of Food History. Oxford UP, 2012. [See p.470]

Winterbotham, William. An Historical, Geographical, Commercial and Philosophical View of the American United States, and of the European Settlements in America and the West-Indies. Vol. 3. London: Ridgway, Symonds, Holt, 1795.

Yee, Jennifer. The Colonial Comedy: Imperialism in the French Realist Novel. Oxford UP, 2016.