France embraced works by William Shakespeare (1564–1616) after Voltaire (1694-1778) became enthusiastic about them in the 1720s, and the English have long embraced French food, so it should not cause much of a kerfuffle to mention here that the few French food-related items appearing in Shakespeare’s plays are not all favorable ones.

In the play All’s Well That Ends Well (c.1602), set in France and Italy, the character Parolles talks of “French withered pears” when trying to convince Helena to lose her virginity:

Let me see. Marry, ill, to like him that ne’er

it likes. ‘Tis a commodity will lose the gloss with

lying; the longer kept, the less worth. Off with ‘t

while ’tis vendible; answer the time of request. Virginity,

like an old courtier, wears her cap out of

fashion, richly suited but unsuitable, just like the

brooch and the toothpick, which wear not now.

Your date is better in your pie and your porridge

than in your cheek. And your virginity, your old

virginity, is like one of our French withered pears:

it looks ill, it eats drily; marry, ’tis a withered pear.

It was formerly better, marry, yet ’tis a withered

pear. Will you anything with it?

(1.1.158–70).

The Royal Shakespeare Company’s website has an entry on its page “Slang and sexual language” which suggests that beyond the notion of oldness “French withered pears” could have been interpreted by the audience of Shakespeare’s time to mean that particular part of the woman’s body being syphilitic. These words said by Parolles might not exactly endear him to a French audience.

▀▄▀▄▀▄

Shakespeare’s history play Henry VI, Part II (c.1590/1594) begins with the 1445 marriage of Henri VI to Margaret of Anjou and makes its way to the 1450 popular revolt led by Jack Cade. When the character Jack Cade establishes himself as mayor of London, a position which he holds on to for only a very short while, he says the following:

Now is Mortimer lord of this city. And here, sitting

upon London Stone, I charge and command

that, of the city’s cost, the Pissing Conduit run

nothing but claret wine this first year of our reign.

And now henceforward it shall be treason for any

that calls me other than Lord Mortimer.

(4.6.1–6).

By “claret” Jack Cade would be referring to reddish wine from Bordeaux, and the “Pissing Conduit” mentioned is a narrow conduit near the Royal Exchange. When the historical Henri VI’s coronation was celebrated, conduits large and small ran with wine, and here Jack Cade’s words are parodying that. It is possible that this imagery also has French roots, according to the commentator George Steevens (1736-1800) who in an 1807 edition of Shakespeare’s plays links Jack Cade’s speech to a 1453 feast given by Philippe le Bon (1396-1467) where a statue “ ‘pissait eau-rose’ ” (239n3).

It should be noted that relations between France and England were frayed if not outright antagonistic at the time of the historical Jack Cade’s revolt: the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453) had been dragging on for more than a hundred years and would end three years later. In terms of business, the 1152 marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1204) to the English king Henry II (1133-1189) had opened up a large market for Bordeaux vintners. At the time that Shakespeare was writing, claret was still an imported favorite in England, among those who could afford it—it was at least ten times more expensive than beer.

▀▄▀▄▀▄

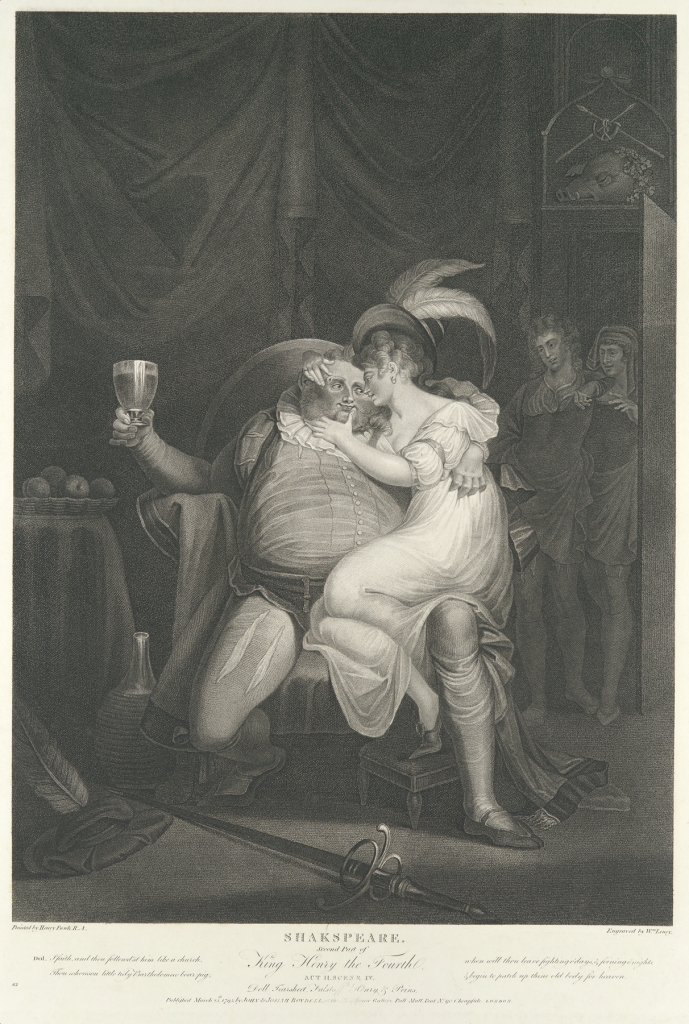

In the history play Henry IV, Part II (c.1597) Shakespeare has the character Doll Tearsheet simultaneously insult and compliment her soon-to-be lover Falstaff:

Can a weak empty vessel bear such a huge full

hogshead? There’s a whole merchant’s venture of

Bordeaux stuff in him. You have not seen a hulk

better stuffed in the hold. —Come, I’ll be friends

with thee, Jack. Thou art going to the wars, and

whether I shall ever see thee again or no, there is

nobody cares.

(2.4.63-9).

The large amount of Bordeaux wine that the humorous character Falstaff drinks can be comparable to the amount of Chinon wine imbibed by Rabelais’s character Gargantua (35), as viewed by Jean-Robert Pitte in Bordeaux / Burgundy: A Vintage Rivalry (2008).

Engraver: William Satchwell Leney (1769–1831). Artist: after Henry Fuseli aka Johann Heinrich Füssli (1741–1825). Doll Tearsheet, Falstaff, Henry and Poins (Shakespeare, King Henry IV, Part 2, Act 2, Scene 4). 1795. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. → https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/365589

▀▄▀▄▀▄

References & Suggested Reading

“Claret wine.” A Shakespeare Glossary. 1911, https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.03.0068%3Aalphabetic+letter%3DC%3Aentry+group%3D8%3Aentry%3Dclaret+wine . Accessed February 2018.

Dobson, Michael, et al., eds. The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Folger Shakespeare Library. All’s Well That Ends Well from Folger Digital Texts. Ed. Barbara Mowat, Paul Werstine, Michael Poston, and Rebecca Niles. Folger Shakespeare Library, February 2018. https://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org/?chapter=5&play=AWW&loc=line-1.1.158.

– – – . Henry IV, Part II from Folger Digital Texts. Ed. Barbara Mowat, Paul Werstine, Michael Poston, and Rebecca Niles. Folger Shakespeare Library, February 2018. https://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org/?chapter=5&play=2H4&loc=line-2.4.63.

– – – . Henry VI, Part II from Folger Digital Texts. Ed. Barbara Mowat, Paul Werstine, Michael Poston, and Rebecca Niles. Folger Shakespeare Library, February 2018. https://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org/?chapter=5&play=2H6&loc=line-4.6.1 .

Hattaway, Michael, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare’s History Plays. Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Hope, Annette. Londoners’ Larder: English Cuisine from Chaucer to the Present. Random House, 2011.

Murphy, Donna N. The Marlowe-Shakespeare Continuum: Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Nashe, and the Authorship of Early Shakespeare and Anonymous Plays. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013.

Nares, Robert. A Glossary: Or, Collection of Words, Phrases, Names, and Allusions to Customs, Proverbs, &c., which Have Been Thought to Require Illustration, in the Works of English Authors, Particularly Shakespeare, and His Contemporaries. London: R. Triphook, 1822.

Pitte, Jean-Robert. Bordeaux/Burgundy: A Vintage Rivalry. Univ of California Press, 2008.

Shakespeare, William. The Plays of William Shakespeare, with Notes, by Johnson and Steevens. Vol. X. Philadelphia: J. Morgan and T.S. Manning, 1807.

“Slang and sexual language.” The Royal Shakespeare Company, https://www.rsc.org.uk/shakespeare/language/slang-and-sexual-language . Accessed February 2018.

Thomas, David. A Visitor’s Guide to Shakespeare’s London. Great Britain: Pen and Sword, 2016.

Trawick, Buckner B. Shakespeare and Alcohol. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1978.