April 3, 1807 was a regular workday for the chef Honoré Julien (1760–1830) and his assistants Edith Hern Fossett (1787-1854) and Frances Gillette Hern (1788-after 1827), both of whom were enslaved. When they were preparing dinner for the president Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) and his guests, “Julien directed Edy Fossett in putting together his specialty of the day, ‘partridge with sausages & cabbage a French way of cooking them.’ . . . He was anxiously watching Fanny Hern stir an egg custard for the centerpiece of the dessert course” (Stanton 50). Thanks to a diary kept by Isaac A. Coles (1780-1841), who was Thomas Jefferson’s private secretary from 1805 to 1809, we know also that more than one dessert was made that day: “For the bottom of the table there were ‘apples inclosed in a thin toast a french dish’ ” (Stanton 51). Honoré Julien became the White House chef in 1801. At the time he had been in the United States for less than ten years, but he was not a total stranger to working for a president: he had worked for four months in George Washington’s kitchen at the end of his presidency (Stanton 42). In 1802 fifteen-year-old Edith Hern Fossett arrived at the White House to work with Honoré Julien, and in 1806 came her sister-in-law Frances Gillette Hern, at the age of eighteen (Stanton 44). Ursula Granger (born 1787) was actually the first of three enslaved women who had worked with Honoré Julien in the White House kitchen, but she had smallpox around May 1801 and was therefore sent back to Jefferson’s Monticello estate. Jefferson’s love for French cuisine was greatly influenced by his post as Minister to France, which began in 1784 and during which he lived in France for around five years. As president of the United States from 1801 to 1809, he regularly hosted dinners where there were on average ten to twenty-five guests.

▀▄▀▄▀▄

In the article “Francophilia, Food, and Freedom at Jefferson’s Monticello” (2014) by Tandra Taylor for the Missouri History Museum’s website, she points out how learning a bit of the French language most likely needed to happen in Edith Hern Fossett’s case and that of Frances Gillette Hern: “I can speculate that these enslaved bondspeople acquired some sense of the French language necessary to articulate components of the recipes (especially that for which there is no English equivalent). They also gained knowledge of French technology of the time. While many enslaved cooks in the American South toiled over large, hot, open hearths, those who worked at the White House and at Monticello used a built-in stew stove, which is easier to control the temperature than a large fireplace.”

▀▄▀▄▀▄

Praise for the food served at Jefferson’s White House came from myriad guests. “ ‘Never before had such dinners been given in the President’s house,’ recalled one Washington resident. ‘The dinner was excellent,’ wrote Benjamin Latrobe, ‘cooked rather in the French style (larded venison), the dessert was profuse and extremely elegant’ ” (Stanton 187). Margaret Bayard Smith (1778-1844), who wrote novels and biographies, in addition to chronicling life in Washington (D.C.), described dinners at Jefferson’s White House in the following way: “republican simplicity was united to Epicurean delicacy” (Smith 391-392). Her husband was Samuel Harrison Smith (1772-1845), publisher of the National Intelligencer newspaper. More recently, in the 2012 article “Meet Edith and Fanny, Thomas Jefferson’s Enslaved Master Chefs” by Jesse Rhodes for the online Smithsonian Magazine, the historian Leni Sorensen is quoted as saying the following about Edith Hern Fossett and Frances Gillette Hern: “ ‘They were at the absolute top of the chef’s game,’ says Sorensen. ‘But because they were women, because they were black, because they were enslaved and because this was the beginning of the 19th century, they were just known as ‘the girls.’ But today, anyone with that amount of experience under their belt would be Julia Child.’ ”

▀▄▀▄▀▄

The Jefferson White House imported many foods from France. According to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation’s Monticello website, “[a] large shipment received from Bordeaux in 1806 included olives and olive oil, anchovies, three kinds of almonds, artichoke hearts, tarragon vinegar, Maille mustard, seedless raisins, figs and prunes, Bologna sausage, and a Parmesan cheese.” The website also notes the following about a December 1803 dinner: “At that December 1803 dinner Plumer was benefiting from Jefferson’s decision to turn from American merchants to European producers. ‘The meanness of quality, as well as extravagance of price of the French wines which can be purchased in this country have determined me to seek them in the spot where they grow,’ he had written in May to his Paris agent. Shortly before the dinner of Federalists attended by Plumer, the presidential wine cellar had received additions of still Champagne, Chambertin Burgundy, Château Filhot sauternes, and Château Rausan Margaux.”

▀▄▀▄▀▄

After Jefferson’s presidency, Honoré Julien stayed in Washington to open a catering business, and he then passed his culinary knowledge down to his son Auguste, who later on had the opportunity to cater banquets for the eleventh president of the United States James K. Polk. In the case of Edith Hern Fossett, she too had passed down her knowledge about fancy cooking to two of her sons, Peter and William, who became important caterers in Cincinnati, Ohio: “By the 1870s [Peter Fossett] had established his own catering company, with a notable collection of china, linen, and silver purchased from a retiring caterer. Fossett’s firm, in which other family members participated, was described as ‘the most prominent’ catering establishment of the period, and Fossett himself as ‘the indispensable major domo at wedding feasts and entertainments.’ It seems probable that some of Edith Fossett’s French recipes from her years in the White House and Monticello kitchens might have been prepared and served by her sons at the banquets of the city’s wealthy residents” (Stanton 203-204).

▀▄▀▄▀▄

It would have been interesting if Edith Hern Fossett and Frances Gillette Hern had had the opportunity to write down some of their thoughts about working with Honoré Julien. Lacking this type of source (as the vast majority of enslaved people in America were prevented from learning how to read and write), one can still ask if there are diaries, letters, chronicles, or family histories written by other people out there that haven’t been combed through yet for more information about the White House experience of these three essential workers. There is a letter dated May 6, 1809 to Jefferson in which the former White House maître d’hôtel Étienne Lemaire (died 1817) expresses confidence that Edith and Frances will be able to cook French-style dishes at Monticello: “Edy and Fanny are both good workers, they are two good girls and I am convinced that they will give you much satisfaction” (translation from the Founders Online website). In the case of James Hemings (1765-1801), another of Jefferson’s slaves who had learned French cooking, first with a French chef in Annapolis, Maryland, then in Paris as well as at the Château de Chantilly, paying for French lessons out of his own pocket, there has already been a number of works published recently that explore his situation (see the “Suggested Reading” list below).

▀▄▀▄▀▄

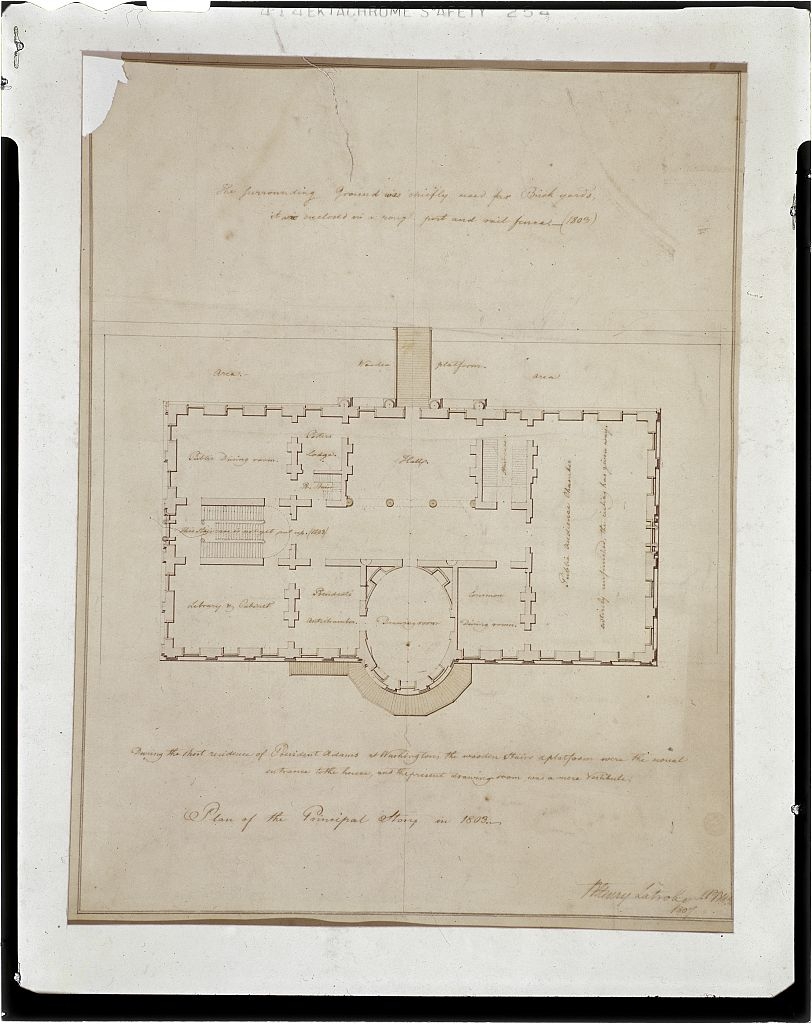

Here are two objects that can be thought of as linking Honoré Julien, Edith Hern Fossett, and Frances Gillette Hern with the many people who were served petits fours and other wondrous foods at Jefferson’s White House:

Porcelain dinnerware used at the White House during Thomas Jefferson’s presidency, imported from China circa 1790. The White House Museum. https://www.whitehousemuseum.org/furnishings/china/china-room-china-Jefferson.jpg

Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764-1820). The White House (“President’s House”) Washington, D.C. Principal story, measured floor plan, 1803, 1807. The Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/item/2001698951 . Public Domain in the US.

▀▄▀▄▀▄

References & Suggested Reading

Coles, Isaac A. Isaac A. Coles diary, 1806-1809. Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Washington, D.C.

Craughwell, Thomas J. Thomas Jefferson’s Crème Brûlée: How a Founding Father and His Slave James Hemings Introduced French Cuisine to America. Quirk Books, 2012.

DeWitt, Dave. The Founding Foodies: How Washington, Jefferson, and Franklin Revolutionized American Cuisine. Sourcebooks, Inc., 2010.

Fowler, Damon Lee, editor. Dining at Monticello: In Good Taste and Abundance. University of North Carolina Press, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, 2005.

“French Influences on American Food.” The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. Edited by Andrew F. Smith. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Gordon-Reed, Annette. The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family. New York: WW Norton & Company, 2009.

“Heirlooms of the Nation in the Cabinets of the White House.” Arts and Decoration, Volume XVII, no. 6, October 1922, pp.410.

Julien, Honoré. “Honoré Julien to Thomas Jefferson, 1 January 1810.” Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-02-02-0084

Kahn, Eve M. “All the Presidents’ Meals: White House Dinnerware.” New York Times, 10 July 2015, p.C20.

Lemaire, Étienne. “Étienne Lemaire to Thomas Jefferson, 6 May 1809.” Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-01-02-0156

McElveen, Ashbell. “James Hemings, Slave and Chef for Thomas Jefferson.” New York Times, 4 February 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/05/opinion/james-hemings-slave-and-chef-for-thomas-jefferson.html

“Official White House China: From the 18th to the 21st Centuries.” The White House Historical Association, 2016. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/official-white-house-china-from-the-18th-to-the-21st-centuries

“Once the Slave of Thomas Jefferson.” Frontline, PBS, 1898 January 30, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/jefferson/slaves/memoir.html

The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series. Edited by J. Jefferson Looney. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004-. 3 vols.

“Peter Fossett.” Ohio History Central. https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Peter_Fossett

Rhodes, Jesse. “Meet Edith and Fanny, Thomas Jefferson’s Enslaved Master Chefs.” The Smithsonian Magazine, 9 July 2012, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/meet-edith-and-fanny-thomas-jeffersons-enslaved-master-chefs-1121916/#GVh9o1MoaaJUGsgC.99

Smith, Margaret Bayard. The First Forty Years of Washington Society: Portrayed by the Family Letters of Mrs. Samuel Harrison Smith (Margaret Bayard) from the Collection of Her Grandson, J. Henley Smith. Edited by Gaillard Hunt. New York: Scribner, 1906.

Sorensen, Leni. “Fosset and Hern: Putting Names to Monticello Cooks.” The Kitchen Sisters, 2006, https://www.kitchensisters.org/hidden_kitchens/herculeshemings_story27.htm#jeffersonscook

Stanton, Lucia C. “Those Who Labor for My Happiness”: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. University of Virginia Press, 2012.

Taylor, Tandra. “Francophilia, Food, and Freedom at Jefferson’s Monticello.” The Missouri History Museum, 17 February 2014, https://www.historyhappenshere.org/node/7493

Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc. “Dining at the President’s House.” Monticello, Home of Thomas Jefferson, 1974/2008. https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/dining-presidents-house

– – – . “Dining with Congress.” Monticello, Home of Thomas Jefferson. https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/dining-congress

– – – . “Edith Fossett.” Monticello, Home of Thomas Jefferson. https://www.monticello.org/site/plantation-and-slavery/edith-fossett

– – – . “Étienne Lemaire.” Monticello, Home of Thomas Jefferson. https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/%C3%A9tienne-lemaire

– – – . “Peter Fossett.” Monticello, Home of Thomas Jefferson. https://www.monticello.org/site/plantation-and-slavery/peter-fossett

“White House China Collection.” The White House Museum. https://www.whitehousemuseum.org/furnishings/china.htm