Pear trees were a distinguishing feature of aristocratic gardens in France during the fifteenth century, but it was under the reign of Henri IV that this luxury fruit became even more prominent. When the Edict of Nantes (1598) ended the religious wars between Catholics and Protestants, Henri IV immediately set out to rebuild the country’s agriculture. The man whom he put in charge of developing nurseries along the Loire River up to the Loiret River was Pierre Le Lectier (died 1636). Le Lectier loved pears so much that of the 468 varieties of fruit trees that were planted, 258 of them were pear varieties. The next most abundant type —the plum —did not even come close at seventy-two varieties. This interest in the pear continued on into Louis XIV’s reign, when Jean-Baptiste de la Quintinie (1624/1626-1688) decided to plant more pear trees than any other type of fruit trees in the fruit gardens at Versailles. Even the statue of Quintinie at Versailles shows him holding a cutting from a pear tree. Soon enough, seventeenth-century England began to imitate the French in planting pear trees.

▀▄▀▄▀▄

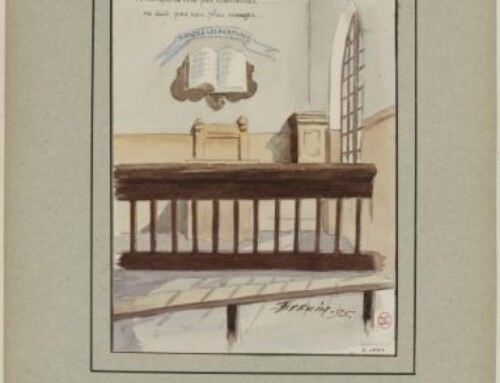

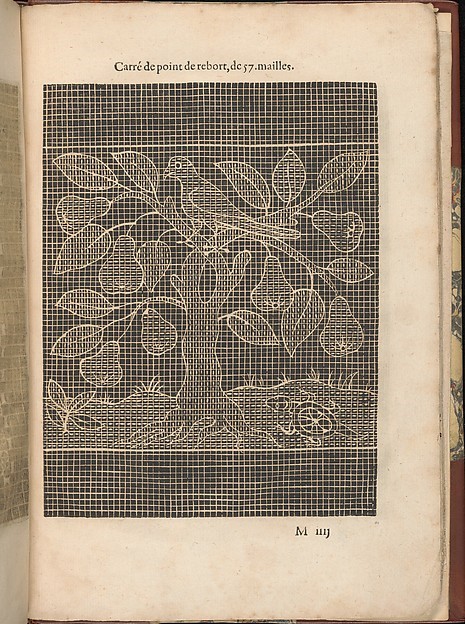

Is it surprising that pears crossed into the realm of ladies high fashion in France? In a pattern book for lace called Les secondes oeuvres, et subtiles inventions de lingerie du seigneur Federic de Vinciolo Venitien (1603) by Federico de Vinciolo (active Paris, ca. 1587-1599) and dedicated to Henri IV’s sister Catherine de Bourbon (1559-1604), there is a design that consists of a pear tree laden with fruit.

Federico de Vinciolo (active Paris, ca. 1587–99). Les Secondes Oeuvres, et Subtiles Inventions De Lingerie du Seigneur Federic de Vinciolo Venitien, page 48 (recto), 1603. Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/662940

Vinciolo had left Venice to work for the French court of Catherine de Medicis (1519-1589), and his first pattern book was acclaimed throughout Europe: Les singuliers et nouveaux pourtraicts du seigneur Federic de Vinciolo Venitien, pour toutes sortes d’ouvrages de Lingerie (1587, published in Paris). The demand for lace grew quickly, even though “[t]he sumptuary laws set out . . . to forbid the wearing of lace to nearly all the social classes except the highest— the royal family and nobles above a certain rank— or at least to dictate its size and position on clothes in the minutest detail” (Kraatz 22). Louis XIV’s minister of finances Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683) became intent on making France more competitive than Venice and Flanders in producing lace. Foreign-made lace was prohibited by law in 1660, and a 1665 decree enabled Colbert to establish numerous factories. Part of his strategy consisted of threatening to punish the families that did not want to let their daughters go into town to become apprentices at the factories! Colbert saw success in less than ten years. The workforce was still badly affected, however, when “the revocation of the edict of Nantes in 1685 struck a heavy blow to the French industry, especially in Normandy, where many Protestants who had worked at lace were forced to disperse to other parts of Europe. The population of lace makers in this region was reduced by half, a situation which profited not only Venice but Flanders” (Kraatz 52).

▀▄▀▄▀▄

Pears and lace are again markers of high social status in a print from 1690 that depicts a woman of that era.

Octobre. Une femme assise prenant dans un panier une poire, 1690. Bibliothèque nationale de France, https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41504843x

▀▄▀▄▀▄

An 1855 engraving for the magazine Petit Courrier des Dames shows a lady considering a pear that she may want to add to her fruit basket. The viewer as a current or potential client of the House of Paquin would want to choose this dress just as the lady is choosing that particularly good pear. The pear can also be seen as enhancing the lady’s dress colorwise.

Monsieur Carrache (possibly A. Carrache, artist), Hopwood (artist), Madame Leymerie (fashion designer), Madame Dasse (milliner), House of Paquin. Fashion Plate for Petit Courrier des Dames, 1855. The Victoria and Albert Museum, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O576724/fashion-plate-carrache-m/

Jeanne Paquin (1869-1936) headed the House of Paquin for almost thirty years and is considered to be “the first major female couturier, running one of the biggest couture houses of the early twentieth century, employing 2,700 employees at its height. She was also one of the pioneers of the modern fashion business, building her label as an international enterprise —and becoming the first Parisian name to open stores in cities such as London, New York, Madrid and Buenos Aires” (Polan 17). In 1913 Jeanne Paquin was awarded the Légion d’Honneur, becoming the first female couturier to receive such recognition.

▀▄▀▄▀▄

References & Suggested Reading

Jones, Ann Rosalind, and Peter Stallybrass. Renaissance Clothing and the Materials of Memory. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000.

Kraatz, Anne, and Pat Earnshaw. Lace: History and Fashion. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1989.

“L’horticulture Orléanaise.” Corporation de la Saint-Fiacre, 2016. https://stfiacreorleans.fr/index.php/L-horticulture-Orleanaise.html . Accessed 11 October 2016.

Mémoires et procès-verbaux, Tome septième. Société agricole & scientifique de la Haute-Loire. Le Puy: R. Marchessou, 1894.

Morgan, Joan. The Book of Pears: The Definitive History and Guide to Over 500 Varieties. Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2015.

Oghina-Pavie, Cristiana. “Rose and Pear Breeding in Nineteenth-Century France: The Practice and Science of Diversity.” New Perspectives on the History of Life Sciences and Agriculture. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2015. 53-72.

Polan, Brenda, and Roger Tredre. The Great Fashion Designers. Oxford, UK: Berg, 2009.

Sirop, Dominique, and Marie-Christine Hergott. “Paquin: Suivi du catalogue de l’exposition «Paquin—Une rétrospective de 60 ans de haute couture» organisée par le Musée Historiques des Tissus de Lyon: Décembre 1989-mars 1990.” (1989).

Stone, Elizabeth. The Art of Needle-work, from the Earliest Ages; Including Some Notices of the Ancient Historical Tapestries. London: H. Colburn, 1840.